For a brief moment, Don Walker’s love of quail hunting was superseded by his love of coffee.

“I always have a pot going,” he said, getting up from the dining room table to replenish his cup. “I gotta have my coffee.”

Then, back in his chair, the 76-year-old Nixa man sipped and spoke of game birds past.

Talking to Walker about the heyday of quail hunting is like talking to an old musician about the golden age of jazz. You can see the vibrant joy in his eyes when he describes his past experiences; you can hear the deep regret in his voice when he talks about how things aren’t what they used to be.

“I’ve sacrificed a lot of time to go quail hunting,” he said of the pastime he’s pursued for 67 years. “I’d sacrifice my job, I’d sacrifice anything. When it came around to quail season, it just seemed like I had to go.”

When asked about the current status of quail hunting, Walker just shook his head. “It’s sad,” he said. Once, his dogs didn’t have to run more than 50 yards before they found quail. He and his partners would find 18 to 20 coveys a day.

Walker’s feelings are echoed by many hunters across Missouri. They have watched the state’s quail population—and with it, the once-popular sport of quail hunting—go into steep decline. Before deer and turkey ruled Missouri’s hunting scene, quail hunting was the primary activity for many of the state’s outdoor enthusiasts. Throughout most of rural Missouri, it wasn’t Thanksgiving or Christmas unless the family gathering culminated with an afternoon quail hunt.

Walker clearly remembers those glory days.

“Forty years ago, you’d go to a restaurant on opening morning [of quail season] and you couldn’t get in for all the quail hunters. And everybody in the parking lot had dog boxes on their trucks. Down in Douglas County where I always hunted, it would sound like there was a national war going on.”

That’s in stark contrast to his recent hunts.

“The last three or four years I’ve been down there, I haven’t heard a shot,” he said. “Not a one—except my own.”

Hunting statistics back up Walker’s memories. The 426,590 quail harvested during Missouri’s 2003–04 season may sound large, but it doesn’t compare to the 4 million birds taken during the 1969–70 season. Disappearing habitat appears to be the main reason behind dwindling quail numbers.

“Habitat loss is the primary factor for the decline of quail here and nationwide,” said Elsa Gallagher, a wildlife ecologist for the Missouri Department of Conservation.

Gallagher is one of the coordinators of the Missouri Quail Plan. This is the state’s manifestation of the Northern Bobwhite Conservation Initiative, a nationwide plan focused on quail recovery. “In Missouri, brood-rearing, nesting and escape cover are the most limiting factors,” she said.

Changes in farming practices and land use are factors that have heavily influenced Missouri’s quail numbers over the years—to both good and bad effect.

When settlers first began to tame the rugged Missouri landscape, farming was the best thing that could have happened to quail. Crop fields and the waste grain left behind due to inefficient harvesting methods provided bobwhite populations with an abundant food source. The weedy, brushy areas that grew up on the borders of the fields in areas that were untellable became prime areas for nesting, brood-rearing and escape cover.

These environmental changes were welcomed by a bird whose annual life cycle is precarious. Clutch losses from predation and from nest desertion (often caused by heavy rain or severe drought) run high. Nesting failures are common. Few quail live beyond 14 months, and many hens fail to survive long enough to reproduce.

But the female quail that do survive are prolific egglayers. If a clutch is repeatedly destroyed or hens are forced to leave the nest, many will often re-nest several times. Second broods may sometimes be produced by successful early nesting hens. As a result of this resiliency, quail populations can thrive if weather and habitat conditions cooperate.

The land-use practices that created abundant habitat continued in many parts of rural Missouri until well into the 1900s, and the state’s quail population flourished as a result.

In recent decades, farming practices have become much more efficient. Fields are fewer, which means less ground is being worked. Where there are crop fields, many stretch from fence row to fence row with either thin or nonexistent borders in between. The result of these changes is much less habitat available for quail. Walker’s own rural memories are a microcosm of the changes that took place statewide.

“Back when I started hunting, everybody had a tomato patch, a cornfield, a watermelon patch or some kind of field where they tilled the soil. Every farm had them—small farms, big farms, all of them did. It seemed like then, late in the year, weeds would come in after you harvested your tomatoes or whatever your crop was, and it was just quail heaven.”

While it’s not practical to return to the farming methods of 60 years ago, willing landowners can replicate some of the habitat found back then. Cutting timber, disturbing soil occasionally and renewing vegetative succession are the activities that quail responded to favorably in the past. Producing quail habitat today demands the same approaches.

The benefits of this type of management extend far beyond helping quail hunters. It also benefits people who enjoy seeing the vibrant courtship colors of the eastern bluebird or the American goldfinch. It helps individuals (or families) who love to sit in their yards in the early spring and listen to the trill of spring peepers or other types of chorus frogs. It helps curious children who love watching box turtles work their way methodically over the landscape.

The wildlife benefits of quail management are so diverse because management for quail is management for all grassland species. The bobwhite quail is just one creature in a rich mosaic of birds, reptiles, mammals and amphibians that make up a grassland ecosystem. This type of management is an ongoing process.

“Quail habitat management is continuous,” Gallagher said. “Disturbance of grasslands and shrubby areas is necessary to produce quality habitat. Annual disturbance on about one third of your ‘quail acres’ is about right for creating good habitat on our farm.”

Management for grassland species may help domestic,

as well as wild creatures. Using native warm-season grasses as part of a rotational grazing system provides forage that is higher in nutrition during summer than cool-season grasses such as fescue. If it’s cut and baled at the proper time, it can also provide high-quality hay without doing much damage to the habitat needs of the wildlife.

Information about managing for grassland species can be found in two free Missouri Department of Conservation publications: “Wildlife Management for Missouri Landowners” and “On the Edge: A Guide to anaging Land for Bobwhite Quail.” Both books are available at many Department of Conservation offices across the state. Land management information is also available at missouriconservation.org.

“The goal of the Northern Bobwhite Conservation Initiative is to restore quail to 1980s density levels on improvable acres,” Gallagher said. “In Missouri, we have already shown that this can be accomplished both on private and public land. Quail populations respond readily to habitat improvements.

“However,” Gallagher continued, “the battle for bobwhite will be won—or lost—on private land. We [the Missouri Department of Conservation] do not manage enough land to restore quail to the entire state. This must be done on private land, in addition to public land.”

Unfortunately, it’s a battle that will not be won immediately. While it’s true localized quail populations can rebound quickly if weather and habitat conditions cooperate, it’s going to take time for statewide quail numbers to grow and stabilize at higher levels than they are now.

In the meantime, Walker will continue to hunt and hope for better days ahead.

“Oh, he’ll be there on opening day,” said his son,Terry. “If he’s alive and can go—even if he has to get around in a wheelchair—he’ll be there. He lives and breathes quail hunting.”

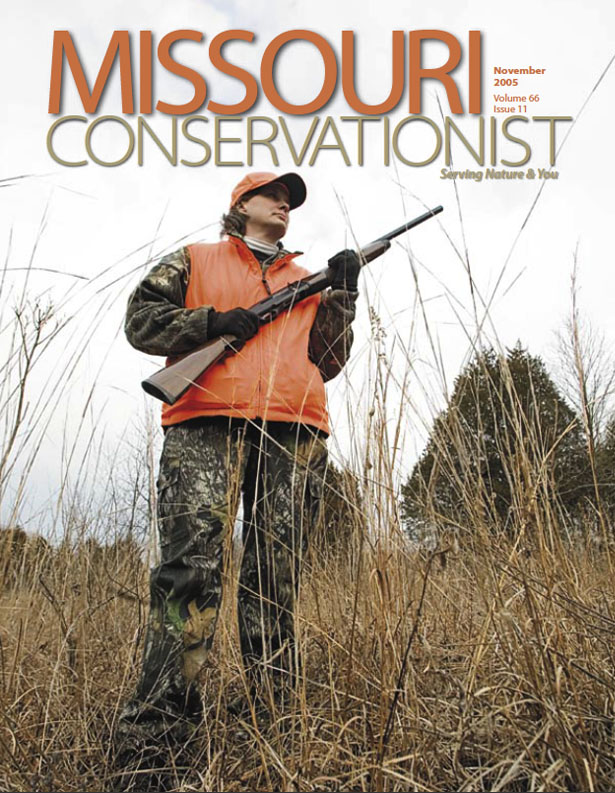

Walker agrees that he has no plans to end his hunts, despite a recent stroke. Come the opening day of quail season, he’ll be on the edge of a field somewhere in southern Missouri, cradling the Model 11 Remington 12-gauge he’s hunted with since he was 13 as he watches his dogs maneuver over the landscape.

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Managing Editor - Nichole LeClair

Art Editor - Ara Clark

Artist - Dave Besenger

Artist - Mark Raithel

Photographer - Jim Rathert

Photographer - Cliff White

Staff Writer - Jim Low

Staff Writer - Joan McKee

Circulation - Laura Scheuler