I often find myself near water when photographing wildlife. It might be a spring branch flowing through a frozen landscape in mid-January or a pond in the warmest week of summer. Regardless of the time of year, my favorite place to photograph critters is at water’s edge. Although some mammals, such as otters and muskrats, are dependent on aquatic habitat, a few others, including raccoons, coyotes, and whitetails, spend a fair amount of time near water as well. They seek water not only to drink but also in search of food and respite from the heat.

Most Missouri mammals are nocturnal, but they are often active at dawn and dusk when the soft light is perfect for photography. I start my day early so I can settle into my photography hide long before the morning light reveals my movements. Typically, I sit in a turkey hunting chair, basically a camouflaged beach chair, with my camera and 500mm lens mounted on a tripod that is splayed over my lap. I use natural cover, such as trees and shoreline vegetation when available, but as a final touch I spread a sheet of military style cut-leaf camo over my camera gear and down to the ground around my legs and boots. It’s a nice set-up because my camera is only a few inches from my face so I can lean my forehead against it and take short naps as I’m waiting for the action to begin.

Here I will share some of my encounters with seven mammals that I’ve photographed from water’s edge. They include the otter, mink, muskrat, beaver, raccoon, coyote, and white-tailed deer. Whether you’d like to photograph some of these critters yourself or simply observe their activities, these anecdotes might increase your chance of success.

River Otter

River otters are full of energy and always on the move. If you see one at all, it will likely be a fleeting glimpse. I’ve had my best luck photographing otters along streams near common latrine sites where they leave droppings and scent markings. Latrine sites are easy to find; just inspect gravel bars for scat that is loaded with crayfish parts and fish scales.

One summer, I had a memorable encounter with two otters along the spring branch at Blue Springs Creek Conservation Area (CA). I had set up early, and a little after sunrise a mama otter with a single pup swam toward me from upstream. I photographed them as they hunted minnows in a scour hole near a huge log. Later, they climbed up on the log where the adult lavished her undivided attention on her lone pup as they groomed and rested. My preparation really paid off that morning.

During winter, a great place to find otters is at an opening in the ice on a lake or pond. I like to set up near the ice hole and wait for the otters to come up for air, preferably with a fish. Sometimes they jump up on the ice to roll and play, which is a sight to see. Otters always find time for frolicking, even when hunting.

My most dramatic otter encounter occurred one morning when I was photographing waterfowl from a dike on the Mississippi River in St. Charles County. I was sitting on a rock at the end of the dike, both rubber knee boots in the water to get as close to the action as possible. Suddenly an otter sprang from the river and landed right between my legs onto what apparently was its favorite rock. I don’t know who was more surprised, but the otter flipped backwards into the water so fast it took a moment for me to realize what had just happened. I’ve often quipped that the otter was so close I could smell fish on its breath!

Mink

Mink live near permanent water along streams, lakes, ponds, and wetlands. Unlike otters, mink are all business — no time for goofing around. Most of my sightings have been when they were hunting for food, usually crayfish, but a mink will pursue any prey within reason. I once saw a mink dragging a carp almost twice its size along the bank of the Meramec River. While hiking the wetland trail at Shaw Nature Reserve in Franklin County, I watched a mink dispatch an unfortunate cottontail only a few feet away from me. When the hunt is on, mink appear oblivious to distractions, including photographers.

Several years ago, I encountered a group of young mink that had begun venturing from their den underneath a sycamore along a waterway in St. Louis’ Forest Park. They weren’t mature enough to be too wary, so I was able to capture some great images as they foraged for crayfish. I’ll never forget how one ran right across my boots on its way back to the den with its catch.

Any time I’m near water, I watch for mink. I’ve even seen them at our tiny farm pond. There’s always a chance of seeing a mink if you keep your eyes peeled.

Muskrat

Muskrats are highly nocturnal and quite skittish. If you’re lucky enough to spot one during daylight, don’t dare move a muscle! Muskrats prefer wetlands, lakes, ponds, and slow-moving streams. I’ve had my best luck with muskrats in spring as they refresh their dens made from cattails and other vegetation. I’ve only had one extended session with a muskrat, at August A. Busch Memorial CA. It sat grooming at the edge of a wetland for several minutes in the golden light of morning. I remember thinking how fortunate I was for the opportunity as I was snapping away.

Every other encounter I’ve had with muskrats has been fleeting, so consider yourself charmed if you ever observe one for more than a few seconds.

Beaver

The American beaver, a much larger rodent than the muskrat, has been one of my “nemesis species” until recently. Beavers are the most nocturnal of all the mammals I’ve photographed. I often see them in the pre-dawn darkness, but they usually retreat to their dens long before sunrise.

My luck changed last spring at Creve Coeur Lake in St. Louis County where I had been flushing a beaver in the dark each morning on the way to my hide. One morning I decided to delay my approach until dawn so I would have enough light for a photograph. As I walked toward my hide, I was delighted to see the beaver, awash in the rosy glow of sunrise, eating bark from a willow stick like corn from a cob. It must have been hungry because it never noticed me as I captured its image from 50 feet away. It finally swam off, none the wiser, after it finished its breakfast.

Raccoon

Raccoons spend much of their time at wetlands, lakes, and streams where they hunt for food, often at dawn. One morning when I was photographing waterfowl at B.K. Leach Memorial CA, a mama raccoon with a large group of kits crossed the wetland near my location. Raccoons have extremely sensitive paws, and I watched as they felt the bottom for crayfish and other invertebrates. I had a similar experience at our small pond in Franklin County, allowing for some up-close images of the hungry raccoons.

Most of my other encounters with raccoons, at least during daylight, have been with young individuals venturing out on their own during late summer. A couple of times I have spotted one in the crook of a tree, napping in the shade. Each time I wondered if the young raccoon was experienced enough to find food on its own.

Coyote

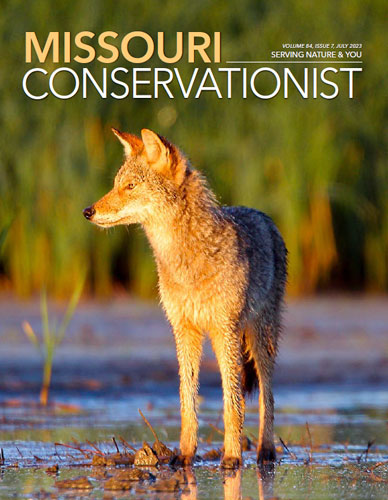

Most people don’t think of water when they think of coyotes, but I frequently see them when photographing near water, especially wetlands. Coyotes are opportunistic and they find easy pickings of frogs, snakes, salamanders, crayfish, and other small prey in wetlands.

One of my favorite coyote images came from a wetland at Columbia Bottom CA just before sunset. The coyote stepped onto the mudflat from a dense stand of cattails and began searching the shallows for prey. I was in my hide nearby and I made several images of the beautiful coyote, its fur golden-red under the setting sun. What a magical moment!

I often see coyotes hunting along the banks of the Meramec River in St. Louis County. I’m never sure what they are looking for, but I bet they enjoy fish remains left by anglers. One morning I watched a coyote follow a whitetail down to the water from a high bank across the river. The deer continued into the water and swam across to my side. The coyote stood at water’s edge and watched as I snapped away from my photo hide. I doubt the coyote was seriously interested in the deer, but the interaction resulted in some nice images.

White-Tailed Deer

Many of my best photographs of whitetails have come from my sessions at water’s edge, often in the fall when deer are on the move due to the rut. I’ve photographed several whitetails, including does with fawns, swimming back-and-forth across the Meramec River to get to favored feeding, breeding, and resting locations. Whitetails don’t hesitate to swim across rivers, even in freezing temperatures. They learn to cross at such a young age it becomes a natural part of their routine. Whitetails aren’t afraid of crossing big water either as I’ve watched them swim across the Missouri River.

Sometimes in summer when I photograph at the wetland at Shaw Nature Reserve, whitetails show up and forage on lily pads, often in water up to their chests. They not only benefit from rich forage but also obtain respite from the summer heat.

I hope these images and anecdotes inspire you to get out and spend some time at water’s edge with your camera or binoculars or both. Remember, you’ll likely be rewarded for the extra effort of making an early start. But if you don’t see a thing, I promise it will still be time well spent.

If you’re looking for a place to watch and photograph wildlife, head to the water

Also In This Issue

Tips for a successful nighttime fishing trip

A gateway to discovering and helping conserve Missouri’s natural resources

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Editor - Angie Daly Morfeld

Associate Editor - Larry Archer

Photography Editor - Cliff White

Staff Writer - Kristie Hilgedick

Staff Writer - Joe Jerek

Staff Writer – Dianne Van Dien

Designer - Shawn Carey

Designer - Marci Porter

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner