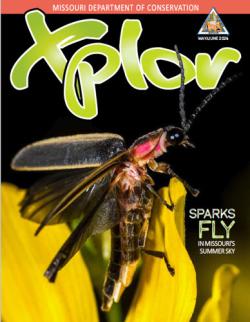

Xplor reconnects kids to nature and helps them find adventure in their own backyard. Free to residents of Missouri.

Stay in Touch with MDC news, newsletters, events, and manage your subscription

Xplor reconnects kids to nature and helps them find adventure in their own backyard. Free to residents of Missouri.

A monthly publication about conservation in Missouri. Started in 1938, the printed magazine is free to residents of Missouri.

Green Ridge, Mo. -- Three research biologists stood motionless, listening for one meek call among the many louder bird songs and trills wafting across a grassy field on a recent spring morning.

Levi Jaster and two assistants spend many mornings searching for Henslow’s sparrows, tiny, four-inch birds weighing less than an ounce that live reclusively in tall prairie grasses. The biologists’ experienced ears picked out the thin chirp from other sounds.

“There he is,” Jaster said, and he directed the crew to focus binoculars and spotting scopes to where a Henslow’s sparrow perched on a prairie grass seed stalk swaying in the breeze.

The team began setting nets to capture the sparrow for research.

Henslow’s sparrows are a grassland bird in decline nationally and considered a “species of concern” by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They could be a future candidate for the federal threatened and endangered species list, though wildlife officials say more research is needed first.

But happily, Henslow’s sparrows are nesting and thriving at Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) wildlife areas near Sedalia, Cole Camp and Green Ridge that are being preserved or restored with native grasses and wildflowers.

The research on this day was at the Bruns Tract west of Green Ridge, which is owned by the Missouri Prairie Foundation but managed by MDC. The research team is also studying the sparrows at other MDC conservation areas managed for grassland plants and wildlife.

Jaster, of Concordia, Mo., is a graduate student at Emporia State University in Kansas. This is his second year of research on Henslow’s sparrows at MDC prairie areas. This summer he’s studying the birds’ usage of fields with non-native cool season grasses compared to former crop fields now replanted with native prairie grasses. The research also serves to gather other data on population trends, nesting and habitat preferences that might be useful in helping all grassland birds in Missouri and other states.

In prior decades, little research was done on Henslow’s sparrows, Jaster said.

Casual bird watchers don’t often see them in the grassy fields. The birds with greenish head feathers and reddish-brown wings streaked with black spend winters at coastal pine savannahs, a tree and grass mix, in the southeastern United States. In the spring they migrate to Midwestern and Northeastern open lands to build nests on the ground. Some Henslow’s sparrow nests are barely bigger than a quarter and hidden in dead or greening grass clumps. Tracking their reproduction is difficult.

Famed 19th century ornithologist John James Audubon named the sparrow for noted English botanist John Stevens Henslow, a teacher of Charles Darwin who founded the science of evolution. But the bird’s famous namesake didn’t lead to research data.

“We know so little about them,” Jaster said. “They tend to stay on the ground. They run on the ground. You sometimes see them carrying food back and forth to the nest, and that’s about it.”

But in spring, males fly up from the ground and cling to waist-high grass and chirp to defend their mating territory.

Research Assistant Jessica Fowler turned on a small digital recorder and played a Henslow’s sparrow mating call to trigger a reply. The team heard a natural “tweet” and soon spotted the sparrow. So they set up “mist nets,” thin netting about seven feet tall from ground to top.

They they walked through the grass and flushed the birds toward the net. The Henslow’s sparrow they heard singing was captured on a second try along with a grasshopper sparrow, which was measured and released.

Research Assistant Keith Waag carefully removed the fragile Henslow’s sparrow from the net. Then the crew began to weigh the bird and measure wing length.

Jaster held the sparrow near his face and blew the downy breast feathers apart to check for signs that it was sitting on eggs and for verification of whether it was male or female. A numbered band was gently placed on the bird’s leg for reference should it be spotted or caught again. Then Jaster held it at arm’s length, opened his hand and the sparrow flew back to the wild.

The crew banded 42 Henslow’s sparrows last year and they are having good success at finding birds this spring. MDC-managed prairies have a diversity of habitat that attracts and sustains grassland birds, he said.

“There’s not much out there beyond these areas for them to use that’s really high quality habitat for them,” Jaster said.

MDC is managing the region’s public grasslands for the eventual return of prairie chickens, which are endangered in Missouri. Jaster’s study is finding useful information about breeding sites that Henslow’s sparrows prefer and what natural habitat provides buffers for them between houses and roads. Such information may be useful for helping prairie chickens, said Steve Cooper, an MDC wildlife management biologist.

“What we’re doing is helping Henslow’s sparrows as we try to help prairie chickens,” Cooper said, “and that makes me feel good.