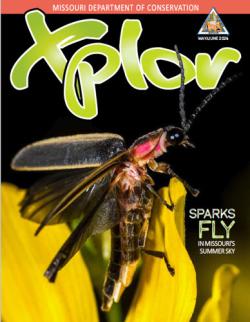

Xplor reconnects kids to nature and helps them find adventure in their own backyard. Free to residents of Missouri.

Stay in Touch with MDC news, newsletters, events, and manage your subscription

Xplor reconnects kids to nature and helps them find adventure in their own backyard. Free to residents of Missouri.

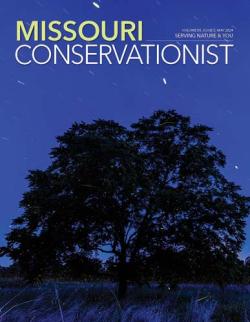

A monthly publication about conservation in Missouri. Started in 1938, the printed magazine is free to residents of Missouri.

PERRY COUNTY, Mo. -- While most southeast Missourians endured temperatures of 21 degrees (Fahrenheit) on Feb. 9, there was a place – still in Missouri - with a much warmer temperature of 58 degrees.

Bruce Henry, a natural history biologist with the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC), enjoyed a balmy temperature of 58 degrees while caving in Perry County to monitor cave wildlife. Henry and other MDC biologists visit caves in the winter to specifically check on the health of local bat populations while they hibernate, as well as survey for other cave dwelling wildlife.

"While many bats will disperse away from the cave during the breeding season, winter gives us a good indicator of their population status," Henry said.

MDC Biologists try to survey known groups of hibernating bats every winter. Bat populations throughout Missouri and eastern states have plummeted in recent years with the introduction of White-nose Syndrome. White-nose Syndrome is fatal to some, but not all bats.

"Our Missouri bats have suffered dramatic losses and we're attempting to take actions that will conserve all we can," Henry said.

Surveys for other cave life are scheduled every few years, with intentions to look for new species, or any large population shifts that may indicate changes in surface water quality. As water quality entering the cave declines, populations of cave wildlife also decrease.

Henry said when he surveys the caves, it usually involves about three hours of time underground. For equipment, the biologists use helmets, boots, sturdy gloves, a headlamp (and a spare), batteries, a flashlight, knee pads for crawling on rocky surfaces and his survey equipment.

While enjoying the 58 degree underground weather that day, Henry observed four species of bats: Big Brown, Indiana, Gray, and Tricolored. Other cave life included several cave insect species such as camel crickets, wolf spiders, cave amphipods, cave millipedes, and segmented worms. Four species of amphibians normally found above ground were observed (likely washed down into the cave through a sinkhole): spotted salamander, slimy salamander, pickerel frog, and green frog. Henry also spotted Raccoon tracks hundreds of yards inside the cave.

"Just like us, animals like to find places to stay warm when it's cold out and a cave is a great place for that," Henry said.

Overall, the wildlife Henry witnessed in the cave represents a moderately healthy habitat, meaning the water quality is good and cave life is in balance with land use activities on the surface, he said. However, numbers of hibernating bats are lower in Missouri than in the past, suggesting that White-nose Syndrome has made a severe impact on these valuable mammals. Corn earworm and mosquitoes are two economic and human health pest species that we know bats frequently prey upon, signifying the importance of a heathy bat population.

"Cave conservation starts on the surface with water and soil conservation actions," he said. "Healthy caves require clean water, so any improvements to water quality across the region can benefit caves and cave life."

Henry said people can help cave habitat and water quality the most by not dumping pollutants such as trash, oils, pesticides, and sewage into sinkholes, creeks, streams, and hollows. These easily run into and degrade cave systems, he said. Grassy waterways, buffer strips, and silt fencing can prevent valuable soil from washing into sinkholes and plugging cave systems.

Just as Henry had to return to the cold above-ground temperatures after his day of caving, all of our surface water that runs underground quickly returns to us through our well supply. In the world of caving, what goes down must come up.

Learn more about Missouri caves, bats and other cave wildlife at mdc.mo.gov.